In early-2017 Silvano Samaroli visited Singapore on what would prove to be his last trip. In Southeast Asia, the famed Italian bottler found bars lined with whiskies and rums he had committed to glass decades earlier, along with a community of fans willing to pay handsomely for his finest creations. Today, Samaroli single malts are regularly counted among the best ever made.

Emmanuel is co-owner of the Auld Alliance in Singapore, one of the most impressively stocked whisky bar in the world. In 2018, he published the first volume of his illustrated encyclopaedia Collecting Scotch Whisky. The substantial tome runs to nearly 900 pages, a significant portion of which are given over to Samaroli and other Italian luminaries of the 20th century. “When I wrote my big book, the legendary Italian bottlers were already old and my main goal was to say we didn’t recognise these people enough for what they did,” Dron tells us. “I think these people had a tremendous influence on what the Scotch whisky industry became, they influenced a lot of what everyone is doing today. So when I started my project, the first thing I said was that I wanted to interview Samaroli, Nadi Fiori, Pepi Mongiardini, and Ernesto Mainardi.”

The dons of the Italian whisky scene really came into their own in the early-1980s. Building on the work done by early single malt evangelists like importer Armando Giovinetti and bar owner Edoardo Giaccone they began to approach companies in Scotland looking for casks to bottle. These enquiries from Italy must have seemed curious to Scottish bottlers as what would prove to be the glory years for Samaroli and others were a period hardship and decline for the wider whisky business.

At that time, ground breaking companies like Gordon & MacPhail and William Cadenhead actively marketed single malt but it was a niche offering. Oversupplied warehouses creaked with casks that seemed destined to disappear, un-celebrated into the blender’s vat. Distilleries were closing, firms were consolidating and the whole industry was steeling itself for more hard times ahead. And yet, more than 2,000 kilometres away, there was a vibrant single malt culture and its desire for good whisky was only growing. “Because of a few guys who created this passion for whisky and started to import more diversity, people started to collect and then more people bottled and it created more diversity and more collectors,” Emmanuel says of the Italian whisky renaissance. “In the 1970s and 80s there was a newsletter for whisky collectors already, there were trips organised to Scotland to buy bottles. If you think about Giaccone, in 1969 he was bottling his first official Clynelish at cask strength. 1969, it’s crazy!”

“Still today, if you need to look for an old bottle of Macallan the only market that was importing the old vintages of Macallan was Italy. They had everything being imported, every single malt was available in Italy when the rest of the world was just drinking Chivas and Johnnie Walker. Every pizzeria and small restaurant would have a collection of whisky, they were drinking Ardbeg and Lagavulin 12-Year-Old.”

The pioneering Italians quickly learned how to tap into the nascent collector’s market. As Emmanuel says “I don’t think the first guy to collect whisky was an Italian, but the first culture to collect whisky is Italy.” They promoted single casks, obscure distilleries, and high ABVs. Their whiskies were marketed as stronger, rarer, better looking, and altogether more desirable than anything else available at the time. It was a period of immense creativity when much of our modern conceptions around the single malt category were born. “For me, they are very, very important because they influenced so much. If you take Samaroli for example, he was the first one to really bottle single cask, cask strength whisky. He was buying from Cadenhead but they were bottling everything at 46% and they were not necessarily single casks. Samaroli putting the cask number on his bottles and announcing cask strength editions. That was very special.”

The first whiskies Samaroli released after an initial run of Cadenhead malts was the 1981 ‘Never Bottled’ series. Sometimes referred to as the ‘flowers’ series for the colourful labels designed by the man himself. It featured casks from distilleries like North Port, Coleburn and Milburn – quite possibly the first commercial bottlings of these whiskies ever produced. Throughout the 1980s, Pepi Mongiardino released lavishly illustrated bottlings with series built around found imagery of marine life, historical costumes and exotic birds. Fernando ‘Nadi’ Fiori bottled then-obscure malts from Ardbeg and Bruichladdich, while Samaroli created his now legendary expressions like the Bowmore 1966 Bouquet and 1970 Laphroaig.

In a very real sense, these bottlings offered a new way of looking at whisky. The Scotch whisky industry had by-and-large adapted to produce a mass market product that was consistent and fungible. What the Italians said loud-and-clear was that their bottlings contained precious things that would exist once and never again. It bears repeating that they owed a lot to their forebears who imported the first single malts to Italy, and yet more to their suppliers in Britain, but Mr Dron is right to say that they made a contribution all their own.

The sheer quality of their output in the 1980s and 90s, has led to the widespread assumption that the Italians had it easy. That the abundance of great whisky from the decades prior and the oversupply of casks meant they had their pick of history’s greatest malts. Once again, Emmanuel wants to set the record straight. “It’s not just enough to say it was about the availability, or else many other people would have done it. Of course, it is true that at that time there was much better quality of whisky than today. But to access them it was a long way, and hard, it required a lot of determination. It was not as easy as people think.”

“Today it’s easy, we receive our samples by post, we can easily communicate with an email. But in 1979, how do you know which company to contact? How do you know how to find a cask? You have to travel, you have to go there. When I was researching the book, Minardi was saying he did one of his trips with the scooter, all the way through Scotland. It’s crazy to do that and to make that connection.” One of the things that becomes clear speaking with Emmanuel, is that the Italians didn’t just benefit from being in the right historical moment, their work required vision.

Samaroli’s 2016 book Whisky Eretico is filled with reflections on a life lived with whisky, but they’re not limited to his observations about production and distilleries. The autobiographical work examines single malt as it relates to our systems of ethics and our place in the natural world. The more time one spends in the company of Samaroli, the clearer it becomes that his innovations were not just about strokes of luck or even the advantages innate to a golden nose. Rather, they were informed by philosophy and imagination.

The most obvious contributions the Italians made to the whisky industry are in marketing and presentation, there can be no doubt about this. Limited editions and series with cask and bottle numbers and artwork are such a part of single malt today that it’s hard to imagine a time when they didn’t exist. It’s also reasonable to say that this early collector culture caused whisky enthusiasts around the world to reassess the value of other bottlings – both official and independent – produced back in Britain. Perhaps the greater contribution is the sense of value they applied to Scotch whisky.

“It was because of them,” says Emmanuel “that the industry survived. Because when it was dying in the 1980s, who was promoting the distilleries? When the industry was only interested in bottling blended. They didn’t care to bottle their own whisky as single malt. What gives me a bit of a sour taste, is the fact that nobody ever contacted Samaroli to ask him to become a Keeper of the Quaich. For me, this is a shame of the industry. They should have a special ceremony for these people, they’ve done so much.”

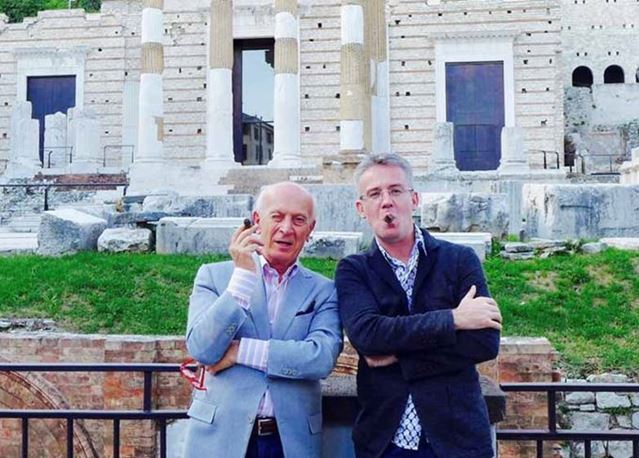

At the Auld Alliance, Emmanuel has carried a concerted effort to champion the work done by independent bottlers of all nations. He is perhaps the person most directly responsible for building the old and rare whisky scene in South East Asia and the Italians have always featured prominently on his bar. Though he might not take credit himself, he also helped inspire the hero’s welcome Samaroli received on that final trip to Singapore.

“I remember he came to my bar and saw all the Samaroli bottles, people came asking him to sign things, I think he was very proud to see that,” Emmanuel begins. ‘I brought him to a cigar bar and when we arrived there my friend the owner asked him what the best bottle he did was and he said ‘for me, my best bottle was not a whisky – it was a rum, West Indies 1948’ and the guy says ‘okay, I’ll open one for you.’ And Samaroli says no because it was expensive but my friend insists that he open it and we drink together and he gave him a cigar form the 1930s. He was very, very proud at that moment, I think. And when I think it was probably his last moment drinking the best bottle… it was a strange time, in a way. I could see he was very proud of that because he was in Asia and he could never have expected that. He could see the love and the respect he has there. That was nice.”

Samaroli was 77-years-old when he passed. He is survived by his wife Maryse and a daughter from a previous relationship. Though the bottles of whisky, rum and brandy that bear his name grow scarcer every year, the legacy of his work will endure long after the last one is gone.